Fiber, by definition, is not absorbable. This has certain specific and important implications for the intestines. First, fiber acts as a vehicle, helping to transport food through the intestines at a healthy rate. The more-rapid transit time that results from fiber in the diet also limits the amount of time cancer-causing chemicals are in contact with the intestine’s cells.

After the body absorbs whatever nutrients it can get from the non-fiber portion of the meal, that food (now referred to as waste) is eliminated via the large intestine with great assistance from fiber. In addition, fiber affects the viscosity of the food, beginning in the stomach, and controls the rate of digestion. Too little fiber results in a too-rapid digestion in the upper intestine.

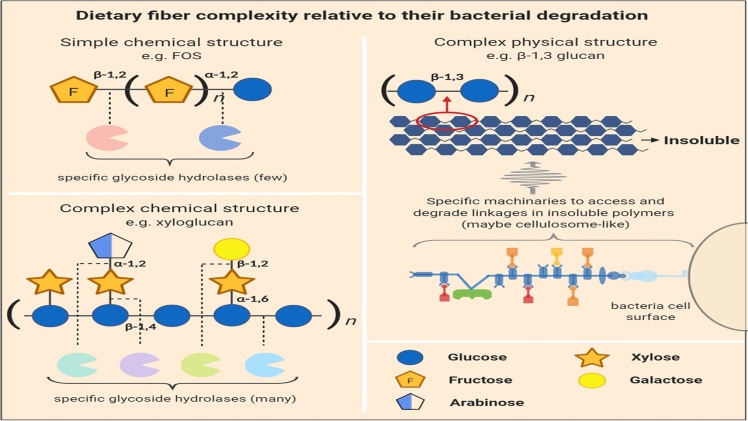

Fiber also is capable of holding water in the intestine, which has an important function of diluting potential toxins, including carcinogens, and preventing constipation. These toxins may also attach to the fiber and be removed from the body. In the large intestine, fiber provides the proper environment for the growth of “friendly” bacteria, which have a very important function.

These micro-organisms ferment some of the fiber substances, improving the health of the intestine and other areas of metabolism. Intestinal bacteria also produce important fatty acids. These fats regather ulate the acid-alkaline balance in the large intestine and in turn control the bacteria themselves.

FULL SPECTRUM OF FIBER

Some fatty acids serve as an important energy source for the cells in the lower intestine. One specific fatty acid, butyric, may also play a protective role against cancer by maintaining a low colon pH and directly inhibiting tumor formation.